|

The ChurchinHistory Information Centre www.churchinhistory.org

The Persecution of Jews in Hungary and the Catholic Church During the German Occupation Part 1

The Hungarian R.C. Chaplaincy, 1991 Dunstan House Acknowledgement Grateful thanks to the Reverend Father David O'Driscoll for his help in preparing this book for publication. Grateful thanks to the publishers for permission to quote from The Holocaust in Hungary: An Anthology of Jewish Response, edited and translated by Andrew Handler. Copyright © 1982 by The University of Alabama Press. Reprinted by permission of the publisher. ISBN 0 9518619 0 5 This internet edition is made available with permission of the chaplaincy by the ChurchinHistory Information Centre. For other publications see our web site:

HUNGARY'S POPULATION

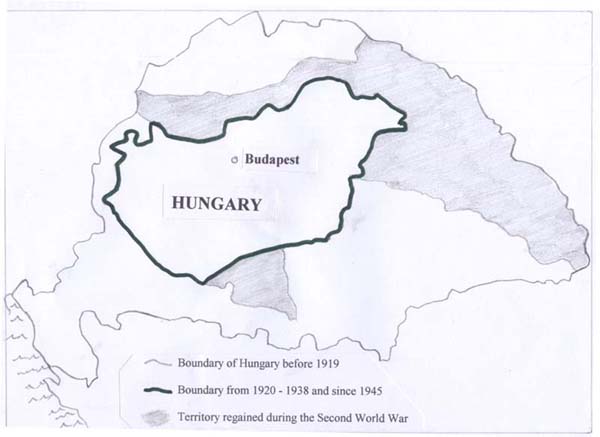

Give no offence to Jews or to Greeks or to the church of God. 1 Corinthians 10:32 Strive even to death for the truth and the Lord God will fight for you, Sirach 4: 33 FOREWORD There have been many books published in English about the Holocaust in Hungary, so why another? Will it not open up old wounds? The answer is not simple. These books have given accounts of the horrors of the deportations, persecution, suffering and deaths of Jewish people. Hardly anything, or very little, has been recorded in them about the heroic attempts of many Hungarians to save Jewish lives during the tragic Nazi occupation of Hungary from 19 March, 1944 to 4 April, 1945. The purpose of this booklet is to draw attention to those, for the most part, nameless and forgotten heroes of the Hungarian resistance. There is, however, another reason for the timeliness of this publication. In recent years reference has been made in some of the media in Hungary and Western countries, and especially in the United States, much of it Jewish owned or controlled, to increasing anti-Semitism in East European countries in the wake of their being freed from Communist tyranny. Among the reasons for such antipathy against Jews may be that there are many people living in Hungary now who remember that the leaders of the short-lived Communist regime there after the First World War in 1919 were Jews. Those who have lived under Communist rule in East European countries after the Second World War know that the surviving Jews attained a privileged status in those countries, especially in Hungary. After the war most of the Communist leaders in Hungary, installed by the occupying Soviet forces, were Jews. Among these were Rákosi, Gerö, Révai, Farkas, Péter. This often resulted in dire consequences for those identified as former Nazis or their sympathisers. More people were executed in Hungary as a result of being thus identified than in all the other former German controlled countries put together with the exception of Yugoslavia. We still hear about the hunting down of former Nazi war criminals; even in Britain legislation has been passed to this effect. But in our time it is vitally important we seek peace and reconciliation, otherwise we shall tear ourselves to pieces. This booklet is motivated by a deep desire for reconciliation between the Jews and Christians of Hungary who have in the past worked together in harmony for generations. The Hungarian cultural, social and economic heritage has been enriched by so many Jewish artists, writers, scientists and experts in many professions. It will be a tragedy if the wounds are not healed. [1] It would help towards such reconciliation if the Jewish people were to recognise and acknowledge that many Christian Hungarians saved the lives of considerable numbers of their Jewish compatriots at great risk to themselves. This is not an attempt at a whitewash. On the contrary, we recognise the fact that the Jewish people suffered terribly in Hungary, as elsewhere, and one is able to understand their bitterness and even their desire for revenge. But there is a need to look afresh at the validity of the numbers of Jews from Hungary said to have been killed during the Nazi occupation, and of the work of other Hungarians to save them. This publication is based mainly on the manuscript of Monsignor Andras Zakar entitled The Twenty-Fifth Anniversary. It has a subtitle: Cardinal Seredi's Defence of the Persecuted Jews. [2] This was discovered recently among a mass of papers left behind by the late Mgr. Béla Ispánki, the chaplain to Catholic Hungarians in Britain. This manuscript, dated 1969/70 (twenty-five years after the fateful events of 1944/45), is a collection of documents dealing with the Catholic Church's efforts to save Jewish lives under the most difficult circumstances. Mgr. Zakar was the archivist of the Archdiocese of Esztergom under Cardinal Serédi, and was later private secretary to Cardinal Mindszenty, so he had unrivalled access to archives and documents relevant to his record. Since it could not be published in Communist Hungary, it appears it was smuggled out of the country and so came into the possession of Mgr. Ispánki. The present publication is a shortened edition of this documentation with the addition of important and relevant facts and reports made by the Hungarian Chaplaincy's team in London, one of whom was personally involved in rescuing Jews in 1944/45. The listing of people or institutions engaged in the rescue operations is limited, of course, by the sources available to Mgr. Zakar at the time of his writing. Thus it is also restricted to the resistance work of Catholic religious communities in the Budapest area. There were many other people who ran risks saving Jews elsewhere in the country. From my own experience, I shall never forget how on 27 November 1944, in my last grammar school year in Vesprém, and when living next to the bishop's house, I witnessed the then-Bishop Jósef Mindszenty being arrested together with some priests and sixteen seminary students. This was on the orders of the town's mayor who was a Nazi sympathiser. The Bishop's crime was that he had stood up in defence of the innocent and protested against the deportation of Jews from Veszprém. In the same town some people were publicly executed for hiding Jews. This booklet reveals another aspect of the story of the Nazi persecution of the Jews in Hungary. It is a memorial to those who, under the most difficult circumstances, tried to live according to the mandate of Christ to offer one's life to save the lives of others. (Mgr.) George Tüttö London, October 1991 Profile of Dr. Andràs Zakar by Mgr. Béla Ispánki, DD Monsignor Ispánki was senior chaplain to Roman Catholic Hungarians in Great Britain from 1957 until his death in London on 9 May 1985. He was sentenced in the Mindszenty show trial in February 1949 to life imprisonment by the Hungarian Communist court the same sentence as Cardinal Mindszenty's. During the Hungarian uprising of 1956 he escaped to the West and he worked first as chaplain to Hungarian refugees in Durham, and then in London. He knew Monsignor Zakar quite well and wrote the following profile of him in a letter to a friend on 4 February 1974: "With regard to Mgr. András Zakar I would like to let you know the following information: "He was born on 30 January 1912 at Margitta (now in Romania). He studied first for a degree in Civil Engineering at the József Nàdor Technical College in Budapest, but just before finishing his four-year course he entered the Central Seminary of Budapest in order to prepare himself for the priesthood. He was ordained priest on 23 June 1940 in Esztergom and graduated at the Theological Faculty of Péter Pázmány University, Budapest, in June 1941. In the summer of 1942 Cardinal Jusztinián Serédi OSB appointed him archivist of the Archdiocese of Esztergom. In July 1943, when I returned from Rome after eight years of studies, Dr. Zakar was promoted to the office of Master of Ceremonies and I took up his previous appointment. In the spring of 1944 he became titular secretary to the Cardinal with duties of a personal nature. We were very close friends, in spite of the fact that he was rather a theoretical type of man, blessed with great tenacity and assiduity, and less with original talents. He was very ascetic; he preferred to sleep on a wooden plank instead of a soft bed, and to eat vegetables rather than any sort of meat. "In March 1946 I left Hungary again for Rome to finish my four-year course for a degree in Philosophy. After my return to Budapest in 1947 we maintained our friendly ties, but we differed very much in our political concept of how to master the extremely difficult political situation which the Church in Hungary, and especially Cardinal Mindszenty, had to face. "On 19 November 1948 Mgr. Zakar was arrested by the Hungarian secret police, just as he left the convent after his Mass to walk back to the archbishop's palace, situated about fifty yards away. "On 26 November 1948 I was arrested by the secret police at my flat in St Emeric's College, the oldest Catholic college in Hungary for the university students of Budapest. "Mgr. Zakar had always been of frail constitution and health. No wonder that he soon broke down under torture and became co-operative with the secret police. As a result he received some preferential treatment in the headquarters of the Hungarian secret police, whilst I and some others involved in the Mindszenty trial had to endure inhuman hardships during our solitary underground detention up to 2 February 1949. "On 23 December 1948 agents of the secret police brought him to the archbishop's palace at Esztergom to show them the place where he had hidden a metal tube containing a collection of very important documents. In October 1948 I had sent a personal message to Cardinal Mindszenty urging him to order the immediate destruction of all sensitive documents which could be useful to the Communists at a trial which might be staged against him. The Cardinal gave instructions to Mgr. Zakar to start this work at once. Mgr. Zakar destroyed many documents but was not willing to destroy some letters and reports which he considered to be of 'historical' interest, thus giving the Communists ample material for a show trial. "On 8 February 1949 the People's Court sentenced Cardinal Mindszenty and myself to lifelong imprisonment. Mgr. Zakar got only six years, which was reduced by the Court of Appeal to four years. He was separated from us in prison. I met him once or twice in prison and had a chance for a chat with him only once. He suffered from severe tuberculosis during his imprisonment. He was due for discharge with remission for good conduct in November 1951, but it was the height of the Stalinist era and no political prisoner could get any remission at that time. So he was interned for a further period of time and was discharged in 1953. He was not allowed to resume his priestly duties, but he was given a small retirement pension in the fortieth year of his life. The Communists looked upon him with suspicion, while his colleagues were afraid of him and avoided every contact with him. "This saintly man had to suffer enormously between two worlds which did not accept him. He made himself useful as a tutor to young people in foreign languages, as a translator, etc. "In October 1956, after Cardinal Mindszenty was liberated from prison, Mgr. Zakar went to him to offer his services as personal secretary. This offer was flatly refused. A few weeks later the new secret police arrested him and questioned him about the conversations he had had with Cardinal Mindszenty during the days of the Hungarian uprising, and concerning the messages I sent to him (i.e. to Mgr. Zakar) from Vienna. As no special charges could be brought against him he was released. So he continued to live on the meagre retirement pension given to him by the government, and on the fees he was receiving from occasional conferences, retreats, etc. "Mgr. Zakar is still living (1974) in private accommodation in the 11th District of Budapest and leads a very secluded life. I have tried to obtain from him a more detailed explanation concerning that famous metal container, about his interrogations at the headquarters of the secret police, etc, but he is afraid to talk or to write. Cardinal Mindszenty writes highly of him in his memoirs to be published shortly. Some Hungarians reject him as a traitor. I think he was very naive in assessing the political situation and the aims of the Communist Party in Hungary; too soft in his capacity as a personal secretary, more soft in front of the secret police. But it is far from me to be harsh towards him. Had he been firmer in holding Cardinal Mindszenty back in some cases, he would have lost his job. Had he been more resistant at the secret police's headquarters, he might not have survived the tortures. In view of the conspiracy charges his sentence was very light and the secret police mentioned him always as an example in various political trials, showing that they can practise mercy. Thus they destroyed his image before a large section of people who were anti-Communist. Mgr. Zakar did not belong to the so-called Peace Priests, and never has tried to turn events to his personal advantage. So neither side in our great national struggle counted or count him as belonging to the Left or to the Right. He is 'suspended in the air', as we say in Hungarian, 'as the coffin of Mohammed'. And that is a very tragic lot for a very good man." Mgr. Zakar [3] died on 31 March 1986, in a home for retired priests at Székesfehérvár, Western Hungary. SOURCES OF INFORMATION I Documents in the Archiepiscopal Archives of Esztergom. II. Documents of the Krumey and Hunsche Trial in Karlsruhe, published in Frankfurt in 1965. III. The Impeachment of Nazism, vol. iii, 1964. (Documents concerning Jewish persecution in Hungary from 26 June to 15 October, 1944). IV. Articles published by the Hungarian Catholic weekly Uj Ember and the monthly journal Vigilia from 1945 to the present day. V. Books: a) The Memoirs of Cardinal Mindszenty. Hungarian edition,1974, Vörösváry, Toronto, Canada. English edition Copyright 1974 by Macmillan Publishing Co, Inc, published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1974. b) Antal Meszlényi, The Hungarian Catholic Church and the Protection of Human Rights, (Szt. István Társulat, Budapest, 1947.) 169 to 178. c) The History of Hungary, (Institute of Historical Research of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest, 1964.) d) Jenö Lévai, L'Eglise Ne S'est pas Tue (The Church did not remain silent) in French,(Ed du Seuil, Paris,1966) (Hungarian Dossier 1944-45). e) Professor C. A. Macartney, October Fifteenth (A History of Modern Hungary 1929-1945) (The Edinburgh University Press, 1957.) f) Andre Handler, The Holocaust in Hungary, (The University of Alabama Press, 1982) INTRODUCTION The Roman Catholic Church in Hungary and the Christian population in general have frequently been accused of having done little or nothing to save the Jews from persecution by the occupying German Nazis and their collaborators from the Hungarian Arrow-Cross (Nyilaskeresztes) Party [4] . To commemorate the 25th anniversary of Cardinal Séredi's death (29 March 1945) his secretary Mgr. Andras Zakar in 1970 compiled a dossier of contemporary documents and relevant writings published at later dates, which prove that the Cardinal, the Papal Nuncio, the episcopate, the clergy and members of religious communities, assisted by many lay people of all classes and denominations, repeatedly risked loss of freedom, faced torture and imprisonment, and even sacrificed their lives in order to help, hide and save persecuted Jews during the most crucial period of recent Hungarian history, from 19 March 1944 to 4 April 1945. For Hungary's treatment of the Jews prior to this period, let independent witnesses be heard: 'Taken all in all, Hungary continued during these months, and right up to March 1944, to be the single country in Europe within arm's length of Hitler in which the Jews enjoyed de facto something approaching civilised conditions. Hungary was a haven of refuge, and not for the Hungarian-born Jews only, for large numbers of foreign-born Jews sought refuge within her frontiers, especially from Galicia after the Germans had occupied it, but also from Slovakia, Romania, etc.' (C A Macartney: October Fifteenth, Part II, p.101) Jenö Lévai, himself a Jew, writes in his book L'Eglise Ne S'est pas Tue(p. 9): 'Never before had there been a pogrom in Hungary. In 1700 there were 12,000 Jews in the country, in 1800 their numbers had risen to 120,000, and at the beginning of World War I to 935,000, i.e 5% of the population' [especially in the wake of the pogroms in Russia towards the end of the 19th century. Cf. Map page 5].

In view of the rapid growth of the Jewish population in Hungary, both in number and influence, it is perhaps understandable that a certain degree of resentment anti-Semitism, if you like developed, resulting in the so-called Jewish Question (Zsidókérdés). Hungary was hoping to resolve this problem justly and humanely, especially through economic restructuring, but the ever increasing pressure, threats and finally occupation by Nazi Germany brought about the tragedy of the Hungarian Jewry. Chapter

I In the early hours of Sunday, 19 March 1944, German troops invaded and occupied Hungary. On the same day, they arrested and imprisoned churchmen, politicians, civil servants, members of the aristocracy, Jews and others who were known to be hostile to Nazism. Parliament assembled, as previously planned, on 22 March, but it was adjourned immediately for an indefinite period. At the meeting only one MP protested against the unconstitutional occupation of the country by a foreign power, but he was soon shouted down by the other members. He was a Catholic priest, Father Jozsef Közi-Horváth, a Christian Socialist. Under the name of the Hungarian Front, opposition parties rallied at once and began to organise resistance to the aggressor. By June they had prepared and issued a proclamation, the main points of which were as follows: "We (the Union of Democratic Parties of the Hungarian Front) address the nation in a most tragic moment of its history. German troops have invaded our country. Our freedom and our lives, the existence of our nation and of future generations are in danger. Neither the threat of captivity, nor death can prevent us from informing the nation of what is going on. We cannot tolerate that at a future peace conference Hungary should again be on the losing side and should suffer far worse consequences than at the Treaty of Versailles (Trianon) after the First World War which dismembered the country. "The programme of the Hungarian Front is as follows: the expulsion of the German conquerors and their stooges, peace with the Allied Powers and the establishment of a free and democratic Hungary. The conduct of the churches of Hungary once again will shine in these sad and tragic times of occupation, and the Hungarian people will always remember that their priests, faithful to the teaching of Christ, stood by them, regardless of the risks to their own lives." "Long Live the Free, Independent, Democratic Hungary!!" Cf. Gyula Kállai, The Movement for Hungarian Independence 1936-1945 (Kossuth Könyvkiadó, Budapest, 1965.) p. 209-213. Persecution of the Jews Under the leadership of Adolf Eichmann, [5] a special section of the Gestapo, consisting of several hundred men, arrived in Hungary at the same time as the German occupying forces. Their task was, with the assistance of Hungarian collaborators and backed by the occupying lances, to carry out the liquidation of the Hungarian Jews whose number had swollen from the pre-war figure of 445,000 to 825,000 according to other estimates to one million. This increase was due to the return of some former territories from Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia between 1938 and 1941, following a series of agreements signed in Vienna, and due to the arrival of many Jewish refugees from neighbouring countries. A provocative and militant press campaign accompanied the first anti-Jewish measures. They had to wear the yellow star, their shops and trading permits were confiscated, their property and money was distributed among the Nazis and other fascist groups. Later they were assembled in houses and ghettos. In May 1944, the deportation of the Jews from all over the country began, except from Budapest, under the pretext of labour service. Under the SS about 437,000 people were crowded into cattle trucks and transported under terrible conditions to various work camps and concentration camps, including Auschwitz, where about 75 per cent perished. There are varying statistics regarding the number of the victims. The newspaper of the American occupying forces in Germany, The Neue Zeitung, under Jewish editorship, in its February 1946 issue, listing the number of Jews killed in European countries, gives the following statistics for Hungary: Jews living in Hungary in 1939 as 403,000; in 1945: 280,000, the number of missing: 123,000. Whitaker's Almanack gives the following numbers: Hungary's Jewish population in 1938: 445,000, in 1946: 200,000. The difference: 225,000. The Recent History Atlas 1860 to 1960 by Martin Gilbert, puts the estimated number of Hungarian Jews murdered as 200,000 out of a Jewish population of 710,000. At a trial at Karlsruhe in 1965, ex-SS Colonel Krumey, one of Eichmann's closest associates, was accused of causing the death of 300,000 Hungarian Jews. He was given a five-year prison sentence, but in 1969 a tribunal at Frankfurt sentenced him to life imprisonment (Cf. Sources of Information II). Other Jewish sources speak of 600,000 Hungarian Jews being killed, and one wonders how such a large figure could be arrived at. The Office of Statistics of the Jewish World Congress, under the presidency of Dr Albert Geyer, gives the following particulars based on data collected by Dr. Szigfrid Roth and Zsigmond Pál Pach. The Jewish population of Hungary, including the additional territories returned to Hungary by the Vienna Treaty, in 1941 was 825,007. On 31 December 1945 the number of Jews living in Hungary is given as 260,500, but by then the additional territories were no longer under Hungarian rule. Was the difference between the above two figures the basis for the alleged number of 600,000 killed? This calculation completely ignores the fact that since 1938, when, with the annexation of neighbouring Austria by Germany, the Nazi threat was at Hungary's doorstep, many Jewish people had left Hungary and settled in other countries, including Britain, U.S.A., Australia, Palestine, etc. Many more had chosen not to return to Hungary after the war. Thousands have settled in Israel. According to Egyleti Elet, the newspaper of the Hungarian-speaking Jews in America, its March 1951 issue stated that 12% of the 2,200,000 Jews living in Israel were from Hungary. This gives the extraordinary number of 264,000. We have no data on the number of Hungarian Jews living in other countries, especially in the U.S.A., but it must be considerable. Perhaps all these were added to the number of 'victims'. Chapter IV will deal with this subject further. Considering the fact that up to March 1944 Hungary was a haven for Jewish refugees from neighbouring countries, it is very difficult to assess the exact number of the victims and of the survivors of the Holocaust. If a doubtful set of figures is repeated by different people many time over, it does not make it any more accurate. Whatever the actual number of those who perished may be, it was a terrible crime and an indescribable tragedy. The purpose of this book is not to establish the exact number of victims, which is a near-impossible task, but to show that the number of victims could have been much greater but for the efforts of the churches and faithful in Hungary who saved many lives, as we shall see in detail in Chapter III. The tragedy of the Hungarian Jews during the German occupation of the country should be viewed in the context of the persecution of the Jews in other German occupied countries of Europe, especially in the neighbouring countries. The whole world was informed during the Eichmann trial of the following facts: 3,400,000 Jews lived in Poland before the war. In 1945 there were 73,955 survivors (97% had perished). In Germany, out of half a million Jews only about 20,000 survived. In Czechoslovakia, 14,489 survived out of 116,551 (Magyar Nemzet, 25 April 1961). In Yugoslavia 60,000 Jews were murdered, and only 6,000 are living there, writes Uj Elet, 1 September 1963. In all the above-mentioned countries the percentage of survival was 13% or less, while about 70% of the Hungarian Jews appear to have survived the Holocaust. For the sake of truth one should note the fact that perhaps the worst pogroms against the Jews were committed in Romania, not so much through deportation by the Germans, but mainly by the members of the Iron Guard. According to the Office of Statistics of the Jewish World Congress, based on the reports made by the joint Anglo-American commission for Palestine, out of a Jewish population of 850,000, the number of those killed is put at 515,000. Whitaker's Almanack gives the number of Jews living in Romania in 1938 as one million, and after the war as 400,000. Gilbert Martin's Recent History Atlas 1860 to 1960 gives the number of 750,000 Jews having been killed in Romania out of a Jewish population of one million (including those from Moldavia and Bessarabia under Romanian rule during the war). While much has been written by Jewish writers about Hungarian anti-Semitism, one hardly hears about Romanian anti-Semitism. Only recently Romania's Chief Rabbi, Moses Rosen, denounced the right-wing newspapers Romania Mare and Europa for their "slanderous, insulting and pogrom-inciting activities". (The Daily Telegraph, 25 June 1991) [6]. Cessation of deportations The news of the mass murder of those who were deported to German concentration camps was spreading, and the Hungarian government was informed by the Allied Powers that not only the Germans, but they too would be held responsible for the deportations, and would be judged after the war accordingly (Cf. The History of Hungary). On 20 June 1944, the Regent, Admiral Miklós Horthy, was informed for the first time, through the so-called 'Auschwitz Minutes' [7] smuggled in from Switzerland, that the Germans were murdering the Jews they recruited for forced labour. He passed on the document to Cardinal Serédi, and also instructed the government to stop the deportations immediately. The role of the Cardinal in stopping the deportation of the Jews was of paramount importance. Ever since the start of the German occupation, he had been trying by various means (meetings and letters) to stop the government's persecution of the Jews alas with very little success. But when he received the documents from the Regent he decided that the moment had come for the truth to be officially brought to the notice of the Hungarian people. He wrote and circulated the joint pastoral letter Successors of the Apostles, on behalf of the Hungarian Episcopate, dated 29 June 1944, the relevant passages of which are as follows: "The successors of the Apostles, that is, the visible head of the Church and all other bishops are the promoters and guardians of God's unwritten, natural, laws and of his written, revealed, laws, especially the Ten Commandments. In this country, all through the thousand years of its history, the Church leaders have always protested whenever someone tried to violate those divine laws, and defended the poor, the defenceless and the victims of persecutions. In these fateful times we, the members of the Episcopate, fulfil our duty when in the name of God we protest against the immoral way in which this war is being conducted. In a war which claims to be just, the killing of defenceless civilians, the bombardment of women and children from low-flying aircraft, the maiming of children through explosive toys dropped from the air, [A reference to air raids by the Allied forces] are all means of destruction which cannot be condoned, because they are against Christian moral laws... "Alas, we also have to point out that whilst in this terrible world conflict we are most in need of God's help and, therefore, should avoid every word and deed which could draw God's wrath upon our nation. We have to admit with deep regret that in Christian Hungary successive measures are being taken which violate God's laws. We do not have to go into details of these measures, because you are very much aware of them yourselves... You know that many of your fellow-citizens among those who share our faith are being deprived of all human rights only because of their racial origin. Innocent individuals, none of whose guilt has been established by legal procedure, are subjected to humiliation and persecution. You would understand this thoroughly only if you yourselves were subjected to it. "We, your bishops, always did and always will, keep aloof from party politics and the pursuit of personal gain. We cannot deny that some members of the Jewish community have had a subversive and destructive influence on the Hungarian economic, social and moral life, and no protest against it was made by fellowJews. We do not doubt that the Jewish question has to be solved legally and justly. Therefore, we do not object to, but approve of, any necessary and justifiable reforms of the economic structures which need to be undertaken for the abuses to be remedied. But it would be culpably defaulting on our moral and pastoral obligations if we failed to defend justice and to protect our citizens and our faithful from being abused solely on the ground of their racial origin. Therefore, during the past months we have incessantly tried by the spoken word and in writing to seek justice and to obtain the abolition of the offensive measures being taken against our fellow citizens. "We are grateful for having been successful now and then in obtaining small concessions, but we have to state with sorrow and deep anguish that we did not get what we most insistently asked for: the suspension of the illegal deprivations and deportations. Confident in the Christian, Hungarian and humanitarian sentiments of the members of the Government, we waited patiently, and did not want to give up hope and refused until now to launch an official protest. "Alas we see that all our efforts and discussions are ineffective on the most important issues. We, therefore, jointly raise our protesting voice and request the authorities to be conscious of their responsibilities before God and our nation, to respect divine law and remedy injustices immediately. The illegal measures they are making not only cause instability and divide the nation at the time of great tension, national calamity and struggle for survival, but turn public opinion of the Christian world against us and what is most important bring God's wrath upon us. "As always we place our confidence in God and ask you, dear faithful people, to pray and act with us to obtain the triumph of Justice and of Christian love. Beware of taking on yourselves the fearful responsibility before God and mankind by approving of, or helping, the execution of the objectionable measures undertaken by the Government. Do not forget that you cannot serve your country's cause by condoning injustice. Pray and work for all our fellowcitizens and especially for our Catholic brethren, for our Church and for our beloved country." In the name of the Hungarian Episcopate Budapest, 29 June 1944. Parish priests and assistant priests were directed to read this pastoral letter from the pulpit on the Sunday following its arrival. The pastoral letter reached all parts of the country, but the 700 copies meant for the Archdiocese of Esztergom were immediately intercepted by government spies and confiscated at the post office. The minister of justice and two of his colleagues rushed to Gerecse, the Cardinal's summer residence, where he was staying. According to witnesses present, they emphasized that due to the 'critical military situation' the Germans threatened to massacre all Jews and to destroy the entire country if the pastoral letter was read out publicly. The Minister asked for the publication of the pastoral letter to be cancelled at once", says the confidential primatial information document No. 5882/1944. "1 replied", said Serédi, "that this was only possible if the Prime Minister assured us in writing that he would stop at once the implementation of anti-Jewish laws and deportations which we violently oppose." After three hours of discussions a compromise was reached: the Government promised to ask the Germans to stop the deportations and to consider the Jewish question a Hungarian internal matter. The letter confirming these promises was brought to Gerecse personally by the Prime Minister, Sztójay, on 8 July, and it was handed over by him to the Cardinal in the presence of Archbishop Czapik of Eger, of Bishop Apor of Györ and of the Vicar General, János Drahos. Whereupon the Cardinal promised to cancel the directive ordering the publication of the pastoral letter because he felt that his protest had been successful. "Thus the first diplomatic battle was won and many hundreds of thousands of lives were saved". (Cf. Lévai, Sources of Information V/d). On 10 July, a further directive (Decree No. 5443) was issued in Esztergom: "I request herewith that on the Sunday following the arrival of Our Pastoral Letter the following message should be read out either before or after the sermon in place of the Pastoral Letter: "On behalf of himself and of all members of the Hungarian Episcopal Conference, Cardinal Séredi, Prince Primate and Archbishop of Esztergom, informs the faithful that he repeatedly contacted the Government concerning measures taken against all Jews, but especially against the baptised ones [8] and that he continues his discussions with the Government." In spite of this directive, the pastoral letter was read out in many churches all over the country, including the Archdiocese of Esztergom... Dr. Zakar's report contains a further document, marked 'strictly Confidential', from the archiepiscopal archives of Esztergom: No. 35/1944, relevant to this period: Cardinal Serédi's Third Circular better to the Episcopate: "Because of unforeseen circumstances, on which I do not wish to elaborate, I decided to publish the pastoral letter I sent to you. It proved to be impossible to discuss it in advance with all of you, but I urgently consulted at least some members of the episcopate. Via the printers and the post office of Esztergom the letter got into the hands of the government, one member of which contacted me asking for the withdrawal of the letter. In return he promised that the government would comply with our demands. On this basis I sent out a telegram requesting the postponement of the publication of the letter. Two days later I received the Prime Minister's letter No. 68/1944, [7 July] a copy of which I enclose herewith, in strict confidence, for your personal information only. On no account may any of its contents be published. 'Your Eminence, 1) On 6 July, 1944, the Government formed a committee for the protection of baptized Jews, which safeguards the interests of all Jews belonging toChristian denominations and acts independently of the Association of Hungarian Jews. [9]2) The Government ordered a thorough enquiry into alleged cruelties and ruthless behaviour in connection with the moving and transportation of Jews... The enquiry established that the reports of atrocities were greatly exaggerated or untrue; but there is no doubt that in some isolated cases they did take place. The Minister of Internal Affairs has ordered the strictest possible disciplinary measures against the perpetrators of the ruthless treatment of Jews and will do the same in future. Furthermore, he has taken measures to prevent similar atrocities in the future. 3) The deportation of Hungarian Jews from Hungary has been suspended until further notice. 4) In the event that the deportation of Budapest Jews might be considered in the future, Christian Jews will be exempt and will remain in the country. It is true that they would have to go on living in separate accommodation, but measures would be taken for them to visit their respective churches and to practise their religion undisturbed. 5) Parents, brothers and sisters of Catholic clergy, the wives and children of pastors of other Christian denominations will be exempt from wearing the distinctive sign (yellow star) and from all its consequences. In informing Your Eminence of these measures I express the hope that in the present circumstances they will satisfy Your Eminence's expectations concerning the implementation of the august principles you advocate.' Döme Sztójay,M.P. "On receiving this letter and following further serious consultations, I issued a radio statement in which I said the pastoral letter only served as information for the clergy and, contrary to the original directive, it was not necessary to read it out in churches. I did all this partly because of the results achieved and partly for other weighty reasons. Although the Pastoral Letter has become widely known without having been read out from the pulpit, I insisted on the publication and reading out in churches of the short radio statement mentioned above, of which directive the Prime Minister has been informed. I will take the opportunity of the Bishops' Conference to give you more detailed information, but I wish to assure all the Very Reverend Members of the Episcopal Conference that I applied the greatest pressure and did all that was possible under the circumstances." + Justinian

Serédi The Impeachment of Nazism (See Sources of Information III) with the period from 26 June to 15 October, 1944. Based on information from abroad it establishes a few facts: Phase One of persecution ends on 6 July, when, in spite of violent counter-measures taken by the occupying forces, the Hungarian Government stopped the deportation of Jews as a consequence of Cardinal Serédi's intervention. Phase Two ends on 22 August, when the Regent, Admiral Horthy, himself ordered the government to tell the Germans that all attempts by them to resume deportations would be resisted by force if necessary. At this stage Eichmann was ordered to leave the country. Phase Three ends on 16 October, when, following Admiral Horthy's attempt to end the war and ask the Allies for an armistice, the Germans forced him to abdicate and eventually took him out of the country. The Impeachment of Nazism, published in 1964, is the first document in Communist Hungary which after twenty-four years mentions some of Cardinal Serédi's writings. But it omits the most important one: the pastoral letter of 29 June. This proves that the Communist authorities were not prepared to reveal the whole truth about the Catholic Church's role during the German occupation. The pastoral letter gave much encouragement and backing to the various organisations working with the Hungarian Front. Catholic printing presses helped with the publication of leaflets which were most successfully distributed during air raids. Unfortunately, the Gestapo discovered the whereabouts of one of them and arrested and imprisoned all the workers, most of whom were priests. Chapter II On 15 October 1944 Regent Horthy decided to end Hungary's war, but his orders were not communicated to the forces in combat. The next day, under German pressure, he resigned and in the power vacuum the Arrow-Cross Party took power under the leadership of Ferenc Szálasi. Jewish persecution, which had slowed down as a result of the Church's and the Regent's energetic stand during the summer, flared up violently. Jews were rounded up again into ghettos and worse was to come. The Hungarian Christian community could not take part in an organised and armed resistance. It had neither the means nor the experience to do that, though here and there in the provinces (e.g. Szeged) and also in the capital some attempts were made at armed resistance. The Church and Christian people, therefore, concentrated their efforts on saving lives. As soon as the Szálasi regime took over Catholic institutions, convents, monasteries and individuals opened their doors to give refuge to many thousands of Jews, only a small percentage of whom were found and taken away by the Nazis. No distinction was made between baptized and non-baptized Jews. They were not asked where they came from. If they had no documents they were provided with some. If they had no money they were admitted free. Several articles in Uj Ember (See Sources IV.) paid tribute to, and wanted to keep alive the memory of, those who so courageously resisted Nazi pressure and stood up for the persecuted. "In autumn 1944 the Swedish Embassy issued 5,000 safe-conduct passes, the International Red Cross 3,000, the Swedish Red Cross 4,000. At the same time 13,000 were issued by the Vatican's representative, the Apostolic Nuncio..." writes Uj Ember in its issue of 15 February 1970. In a few cases these passes were handed over directly to the persecuted, but mostly it was priests, nuns and lay people who delivered them to the fugitives at considerable risk to their own safety. Fr. Francis Koehler, a Lazarist priest, Fr. Rayle SJ, Fr. Frigyes Molnár, Sister Margit Schlachta and many others are listed in the newspaper's articles. Parishes could not offer accommodation, but they acted as information centres, manned by the faithful who found private, secret accommodation for the fugitives. (e.g. One woman living with her cook in a three-bedroom flat at one time had three refugees in hiding: one as a guest, one as a chambermaid, and one as a scullery maid. All three were saved.) All helpers were voluntary, motivated by Christian charity and never for one moment did they expect reward. These modern Pimpernels certainly deserve to be remembered and must be considered first-liners against tyranny. Several priests and nuns were murdered,others suffered torture and imprisonment. Their only crime was sheltering Jews. Since the liberation of Hungary from Communist rule many people have come forward with hair-raising stories of narrow escapes, of ingenious ways of outwitting their often primitive and ignorant persecutors. Just one example: At the time that Raoul Wallenberg for the Swedish Embassy, Waldemar Langlet, the Swedish Red representative in Budapest, co-operated closely with the Sacred nuns in Ajtósi Dürer Sor. Two hundred women and children were hiding among the pupils of the school and in the enclosed part of the convent. The Nazis appeared one night in search of Jews. One of the nuns took them round the premises and when they reached the enclosed part she said: "Do you know what the enclosed part of a convent is ?" They did not. "Only nuns may go in there", she said. "If you try to force your way in you will go to hell." They took fright and hurriedly left. Once again the Jews were safe. On 2 November 1944 the government held the first meeting of the Upper Chamber (corresponding to the British House of Lords) and invited Cardinal Serédi to attend. The session was to discuss Szálasi's constitutional powers, but the official invitation did not contain any is agenda. One of the priest-members of parliament informed the Cardinal in advance that important constitutional questions would be raised. Cardinal Serédi arrived at the House with his secretary and sat down on a sofa in the corridor in the front of the Chamber. Dr. Gyula Kornis, a prominent member of the Upper Chamber, came and sat next to him. While they were talking the secretary obtained a copy of the printed agenda, on which the only item was to be the election and installation of Ferenc Szálasi as leader of the nation and head of state. When the Cardinal saw and read this he realised his presence at this special session would have been interpreted as approval by the Catholic Church of Szálasi as head of state. [10] He at once stood up, led Kornis to the window, and pointed to the inscription on the facade the Law Courts opposite and read Justicia est regnorun fundamentum (Justice is the foundation of nations). Then he hurriedly left the building and returned to Esztergom as a demonstration of his opposition to the illegal proceedings in parliament. Eichmann and his men of the Sondereinsatzkommando returned to Budapest on 18 October 1944 to continue their horrible scheme of the destruction of the Hungarian Jewry, despite the fact that Germany's defeat was by then in sight. The successes of the Allied forces after D-Day on the Western Front, and the closing in by the Soviet troops in the East, left nobody in doubt as to the outcome. Budapest was completely ruined as the result of continuous air raids by the Allies and by the shelling of the Soviet ground forces. Inevitably, very many lives were lost, including numbers of Jews who lived in the ghettos, in the 'sheltered (yellow star) houses' and many of those hiding in convents, monasteries and elsewhere. The most terrible atrocities against Jews on Hungarian soil were committed during the siege of Budapest which came to an end on 13 February 1945 when Russian troops occupied the whole city. About this period Andrew Handler in his book, The Holocaust o f Hungary, (The University of Alabama Press, 1982) writes (page 29 ): "...Even Ferenc Fiala, Szálasi's press chief, admitted that in the absence of law and order in besieged Budapest 'everyone who had acquired a machine gun could become judge and executioner' (Fiala, Zavaros Évek, p.142). Roving gangs of youths who had escaped from correctional institutions, as well as members of the Budapest underworld, took advantage of the prevailing chaos and anarchy and committed grave atrocities. These unsavoury characters not only brandished machine guns but also wore Arrow-Cross armbands. Instead of helping to defend the 'Queen of the Danube' against the 'Mongolian hordes' they perpetrated acts of violence with reckless abandon and wanton brutality against Jews and those whom they branded as politically dangerous. Thus they succeeded in staining whatever military honour and dignity defenders in a hopeless situation are customarily accorded. Those who became the masters of life and death, virtually within shooting range of the advancing Soviet soldiers, not only went on with their bloody, senseless rampage, but actually made preparations to blow up the ghetto so that not a single Jew would survive the fall of Budapest. Remarkably, their plan was foiled by the resolute intervention of General Schmidthuber, commander of the S S Feldherrenhalle Division, who was himself a casualty soon thereafter. The next chapter must be seen against this terrible background. There is some irony in this Hungarian tragedy: it is known that many of the above 'masters of life and death' changed colours overnight and became 'partisans' and then supporters of the Communist tyranny.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||